Three Years Without God, in depth, in black and white

(The film will have special screenings to be announced, and will be streaming in IWant TFC, a.k.a. The Filipino Channel. WARNING: Plot and dramatic high points in the story discussed in close and explicit detail.) I mentioned first seeing Mario O’Hara’s Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos (Three Years Without God, 1976) in the 1990s in a […]

(The film will have special screenings to be announced, and will be streaming in IWant TFC, a.k.a. The Filipino Channel.

(The film will have special screenings to be announced, and will be streaming in IWant TFC, a.k.a. The Filipino Channel.

WARNING: Plot and dramatic high points in the story discussed in close and explicit detail.)

I mentioned first seeing Mario O’Hara’s Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos (Three Years Without God, 1976) in the 1990s in a fading magenta print, then seeing it again — partially restored to its former glory by L’Immagine Ritrovata — in 2016. Earlier this week I finally saw it regraded to black-and-white by ABS CBN’s Film Restoration Project — not necessarily meant to supplant the original, colored copy but to stand alongside it, as an experiment meant to address the fading colors by eliminating them.

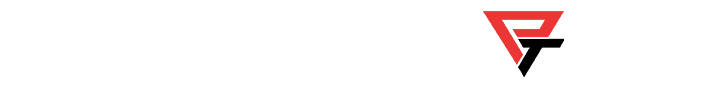

I noted advantages: that the film, set in the Second World War, looks even more like an artifact of the time (black and white was cheaper and more stable, hence used more often under difficult combat conditions); and that O’Hara inserted archival footage of actual fighting and, thanks to the regrading, the documentary segues into drama more seamlessly.

Also, I submit that the more surreal and theatrical effects O’Hara wields throughout the film are only enhanced by black and white. As Luis Bunuel or Maya Deren or Teinosuke Kinugasa might tell us, dreams and nightmares snuggle closer, burrow deeper under the skin when black and white.

And, as Orson Welles liked to say, “(F)aces in color tend to look like meat — veal, beef, baloney.” He thought color distracted the eye, that doing without helped purify the image, allowed us to focus on an actor’s eyes and face.

So (I submit) no actor’s face feels more purified in black and white than producer/lead actor Nora Aunor’s. I’ve always asserted her style of performance was in the tradition of silent films with her expressive face and eloquent eyes; seeing her in largely wordless sequences, in glorious monochrome, confirms my suspicions.

I have always thought O’Hara had a talent for wielding shadows. When Japanese officer Masugi (Christopher De Leon) assaults Rosario (Aunor) in the family pig pen, O’Hara’s camera keeps her face in half-shadow, like a fugitive animal trying to hide in the dark.

The reverse shot also catches Masugi in half-shadow but to opposite effect: the dark slices off the lower half of his face, leaving his plump cheeks bright-lit, suggesting a devil imp that wants a bit of fun — and in fact O’Hara has him pick up a sheaf of straw to tease her with.

Sadism is nothing new to films; what O’Hara brings to the party is an element of mischief, even humor. The cruelty of his characters has a sense of play to them.

Then the church massacre, which demonstrates O’Hara’s skill at action set pieces. A cat-and-mouse hunt between informer and guerrilla in drag ends in a bloodbath.

Note how O’Hara plays with triangular shapes here, the aisle forming a target gallery, the soldiers’ legs planted in wide stable stances, their rifles triangulating as they fire.

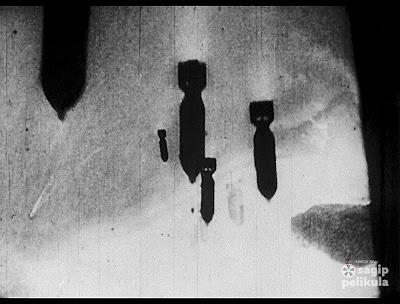

The churchgoers are held hostage, and O’Hara gives us a royal flush of faces: smooth faces, mustached faces, lined faces, cherub-cheeked faces smiling, talking, eating, hugging.

A bit of Vittorio Storaro or Roberto Rossellini post-war neorealism, made convincing by the townsfolk of Majayjay, Laguna, made even more convincing — and moving — by the austerity of black and white.

Then the scene at the bridge — called the Puente del Capricho, the Spanish official’s mocking name for Franciscan Friar Victoriano del Moral’s ambitious project (also nicknamed “Tulay Pigi” (Butt Bridge), for the friar’s tendency to whip the buttocks of the bridge workers).

Rosario stands at the span’s midpoint with her precious burden in arms, and, though you may not realize it, this is also the film’s midpoint and a turning point in Rosario’s life. In color the bridge is a solemn mossy-green presence; in black and white it is a massive shadow looming over the Olla River, the dark and stony riverbed below reflecting the dark and stony state of Rosario’s mind.

Cut to a medium shot of Rosario with her bundle, from which you can see a tiny chubby hand waving; the shot sells you the idea that this is a live baby in her arms and she is standing atop the Puente del Capricho, looking down.

Then the aftermath, where the scene plays out as if in a silent film. When Masugi finds Rosario, she has no words to explain herself, just soft animal noises.

The shame is plain on her face, the tenderness on Masugi’s. The chords of Minda Azarcon’s simple piano melody play in the background.

This is possibly Christopher de Leon’s finest moment, and a high point of the film.

Then the moment when Rosario stood before the crosses of her parents. Not a talky scene — just Rosario and Masugi standing before an overcast sky, the colors (if memory serves me) bleached almost to the point of monochrome — with this regraded copy, all pretense of color has been put to rest, the shot revealed as the bleakest in a bleak film.

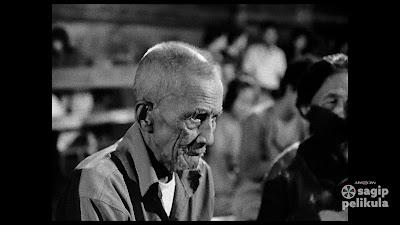

The picture as a whole looks fine but really comes to life in the shadows. The scene of Rosario and Masugi hiding in the nipa hut (Masugi trying to tell Rosario in so many words that he can’t protect her any more, and here they must part) was gorgeous in color; in black and white there’s a severe beauty to the image that recalls Mizoguchi, his camera pulled back a discreet distance just because the onscreen emotions are so strong. Note O’Hara’s use of light and dark — Nora’s dark skin in white shift, against Christopher’s light skin in dark shadow, the contrast heightened in monochrome.

And in these later passages the biblical allegories come to fore. This shot suggests not just Joseph, Mary, and child fleeing Herod, but refugee families fleeing war. Again, the black and white imagery allows a stronger visual link between documentary and dramatized scenes.

The guerrilla attack — the shadows so deep the guerrillas emerge suddenly as if from a black pool, to aim their rifles at the screen.

One guerrilla points a .45 Colt, and O’Hara angles the weapon so that it looks about the size of a cannon.

And three guerrillas against a dark background — made all the more dramatic in black and white — line up in a row, as if in a firing squad.

I mentioned the sense of playful cruelty in O’Hara’s films — recall Masugi and his handful of straw. The guerrillas show they can play that game too, perhaps even better than the Japanese (you might say they learned from the best).

Case in point: Rosario with child, huddled among the cogon grass — in black and white the shadows are deeper and more comforting, a thick velvet blanket to hide Madonna and child. Cogon not bulrushes, but one can’t help but think of the babe Moses, adrift in the wild.

And Rosario looking out from the deep dark tall grasses, discovers the guerrilla’s parting prank.

A parody of an iconic Catholic image.

In the 1970s, blood in Filipino films tended to be distractingly pinkish; in black and white there’s nothing to detract from the moment, the image — against a background of deepest dark — is delivered like a slap to the face, plain and simple with no chance to flinch.

O’Hara’s reply to the guerrillas: not a parody (the timing of the reveal and Minda Azarcon’s solemn music suggest otherwise) but an evocation of the Pieta. And if you’ve seen the statue up close, you’d know it was made in Carrera marble of the purest white, and that this is just that much closer to the Michelangelo masterpiece.

O’Hara shoots Rosario from behind the burning pyre, the flames appearing to flicker round her body — as if she herself stood in hell. Again, black and white heightening the drama of the moment.

And the finale, with Rosario’s former lover Crispin asking the priest: “These past three years — is there no god?” The priest points out the blind man and his palsied brother, and I’m reminded of why O’Hara cast Melvin Flores in the role: “Because he had beautiful eyes.” “You cast him as a blind man for his beautiful eyes?” “Of course!” And of course Flores’ eyes in the severity of black and white shine out all the brighter, remind me of Nazario Gerardi’s in Roberto Rossellini’s The Flowers of St. Francis, also in black and white; possibly O’Hara saw the film. I might even say Flores bears a striking resemblance to Gerardi, though the former’s eyes seem larger (but I maybe be biased)…

Following the priest’s hollow platitudes is O’Hara’s own reply to Crispin, in my book the finest shot in the film, perhaps even all of Philippine cinema: the blind man carrying his paralyzed brother past the gigantic float of Christ, the tiny pair on one side, the float dominating the landscape.

And again, such a theatrical gesture, I submit, works better in black and white, the pair of small figures padding down the aisle making contrast with the grand procession tottering and swaying in the opposite direction, the one having little to say to the other.

Finally, a shot of Flores’ eyes, huge and sightless in black and white. I can think of worse ways to close a film.